Designing the European Restorative Justice award

Handmade and relational

In the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic I was delighted to open my email inbox and find a message from Emanuela Biffi inviting me to discuss a potential design commission for a European Restorative Justice award with the European Forum for Restorative Justice (EFRJ).

Whilst a little daunted, I was excited as this felt like the perfect commission in its merging of two of my passions – design and restorative justice. Occurring during lockdown made the commission even more significant as it was outward looking. As an islander, being asked to design an award that would be presented during an island conference in Sassari, Sardinia was an additional layer of meaning for me. I will return to this connection later on.

The new awards were to celebrate both the twentieth anniversary of the EFRJ, the new EFRJ logo, website and branding, as well as the restorative process itself. These were the reasons why I used the EFRJ logo as my starting point for gathering initial ideas for the design process.

Image source: European Forum for Restorative Justice

The design process I used to create the awards was a design thinking one (the methodology behind how a product or service is designed and produced), which I believe has synergies with the restorative one. There is no one iteration of design thinking but many would see it as containing three basic components that include: the initial concern or inspiration, the development and exploration of ideas, and the implementation of those ideas, including prototyping and trial. Participatory design involves all stakeholders in these three components.

This co-creative involvement is what I aimed to achieve throughout the design process – whether I did or not would be for others to judge but I endeavoured to involve the EFRJ Board members and Executive staff who had been tasked with working alongside me in each stage of the design process. This was from writing the design brief, through designing the initial concepts, to decisions around the construction of the awards, and materials used. A huge thank you to the EFRJ design group who worked with me: Emanuela Biffi, Balint Juhasz, Edit Törzs, Brunilda Pali, Patrizia Patrizi, and Katerina Soulou. The commission was an honour and here is the story behind the making of the awards.

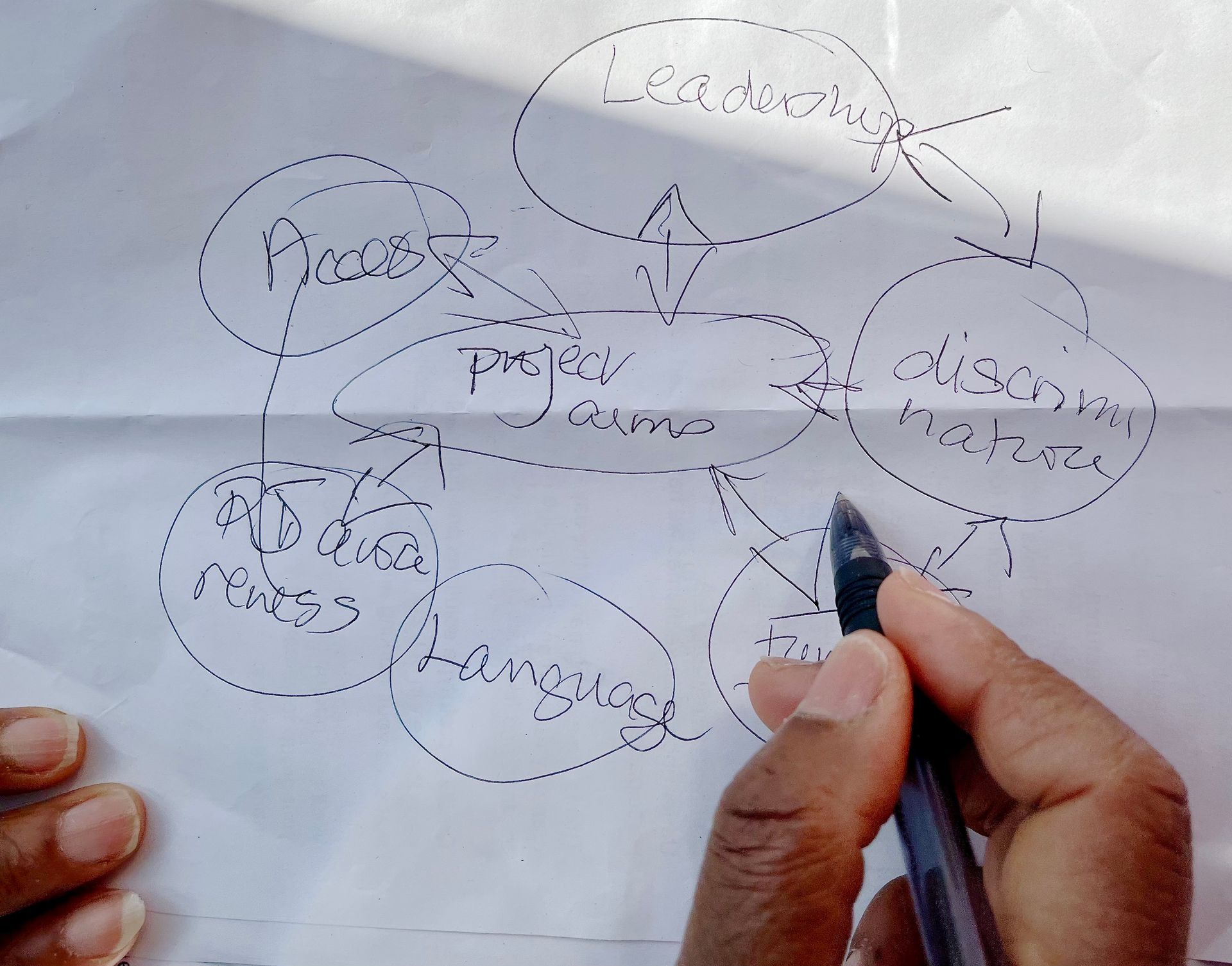

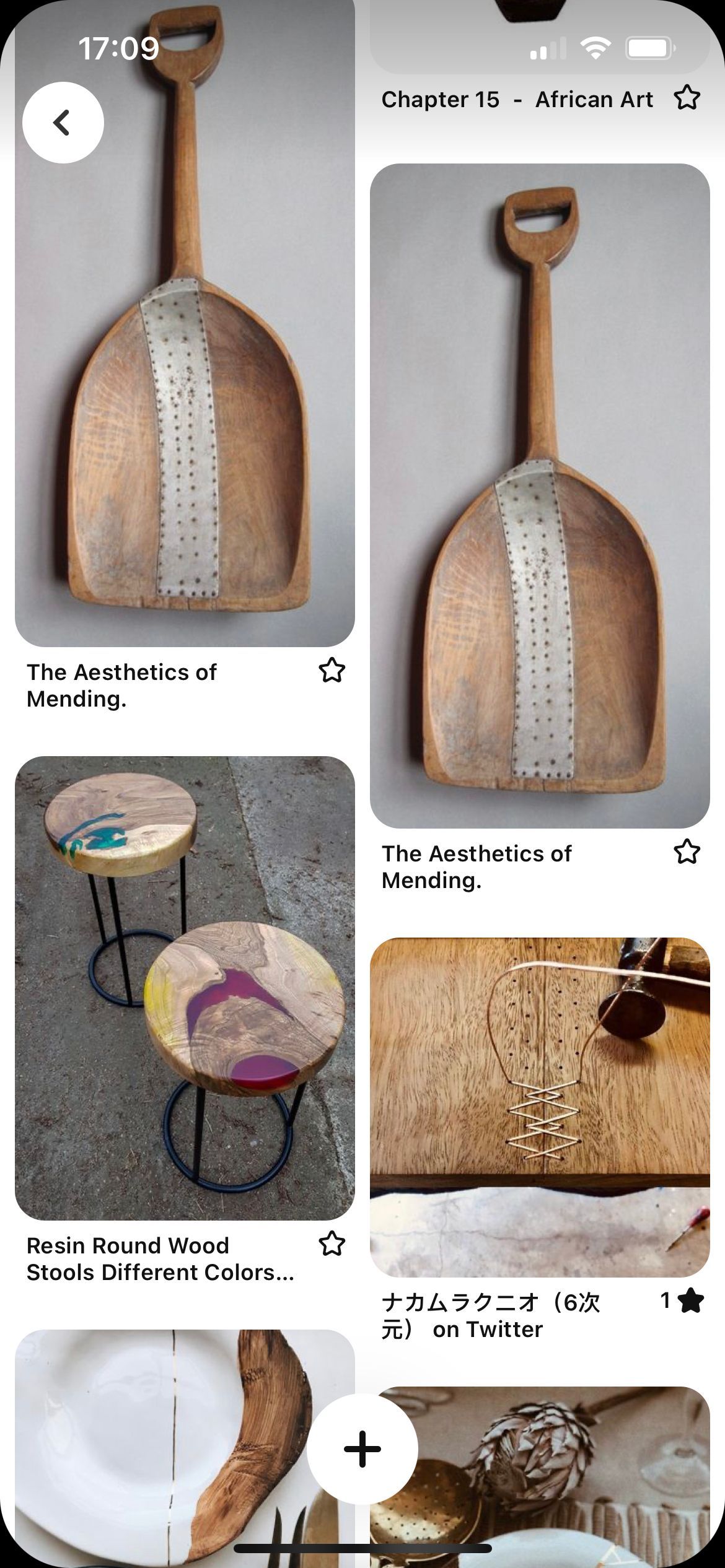

I began by creating a group

Pinterest board for the award. This contained visual images posted by members of the design group as a way of helping me to understand both the aesthetic as well as any functional expectations for the award. You can see some of these in the screenshots below.

Image source: screenshots of our co-creative Pinterest board

From these visual exchanges we were able to develop a design brief that defined the characteristics of the award. These were that the award should be:

- Recognisable, as an award given by the EFRJ only (not simply bought somewhere);

- Meaningful, as the award should reflect restorative justice (its values, its community, its movement, etc.);

- Reproducible/ replicable but unique, as the award is given every two years, but it is produced in a limited edition and personalized for the winner only;

- Decorative and maybe multi-functional, as the award is a “beautiful treasure” to show excellence in the restorative justice field and maybe can be used for other purposes (e.g. talking piece);

- Resistant and long-lasting, as the award will “travel” (from the EFRJ Secretariat to the conference venue to the home of the award winner), and thus should be easy to carry and not fragile.

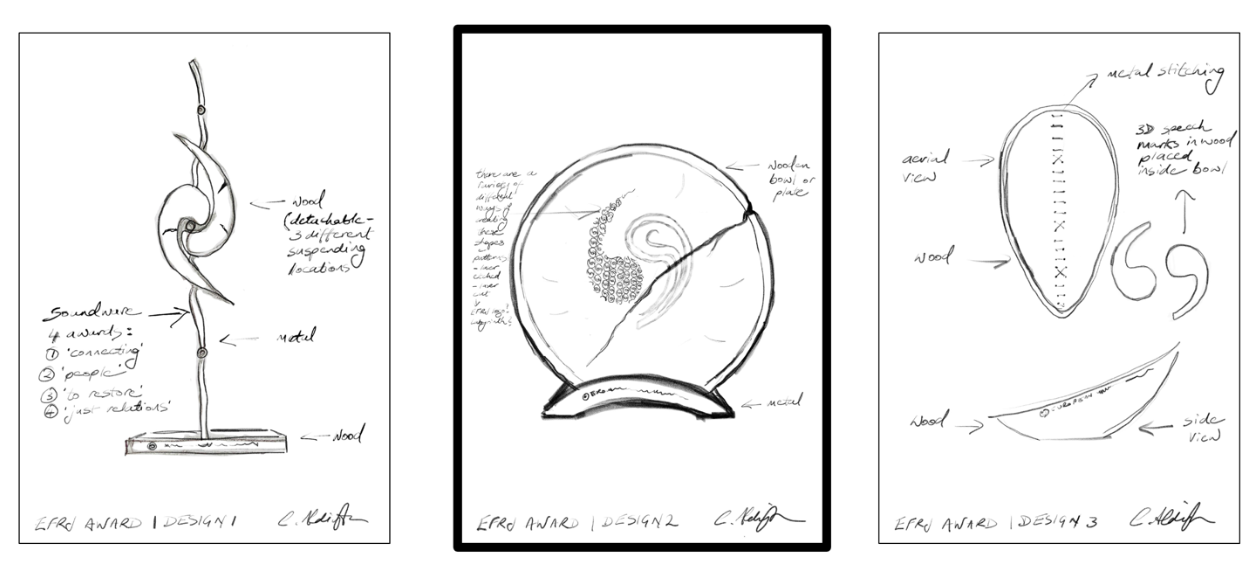

I used these characteristics to inform my initial design ideas based on the EFRJ logo. I dissected the logo and saw it as being comprised of two speech marks as in the image below.

As I did so, I reflected on the significance of speech marks – they seem to define the space of a dialogue. The first speech mark is the start of a conversation, then there is the space in between, and the closing of the dialogue with the second. Or visually they could represent the two perspectives in a restorative conversation expectantly facing each other with a space in between for negotiation, understanding and dialogue. The form of the speech mark is also the same as that of a comma – marking a pause in a conversation, a taking of breath, a space for reflection, or a new idea. I also considered the speech mark, although varying slightly in design in different languages, to be a universal form. It seemed an appropriate form for the basis of the award design.

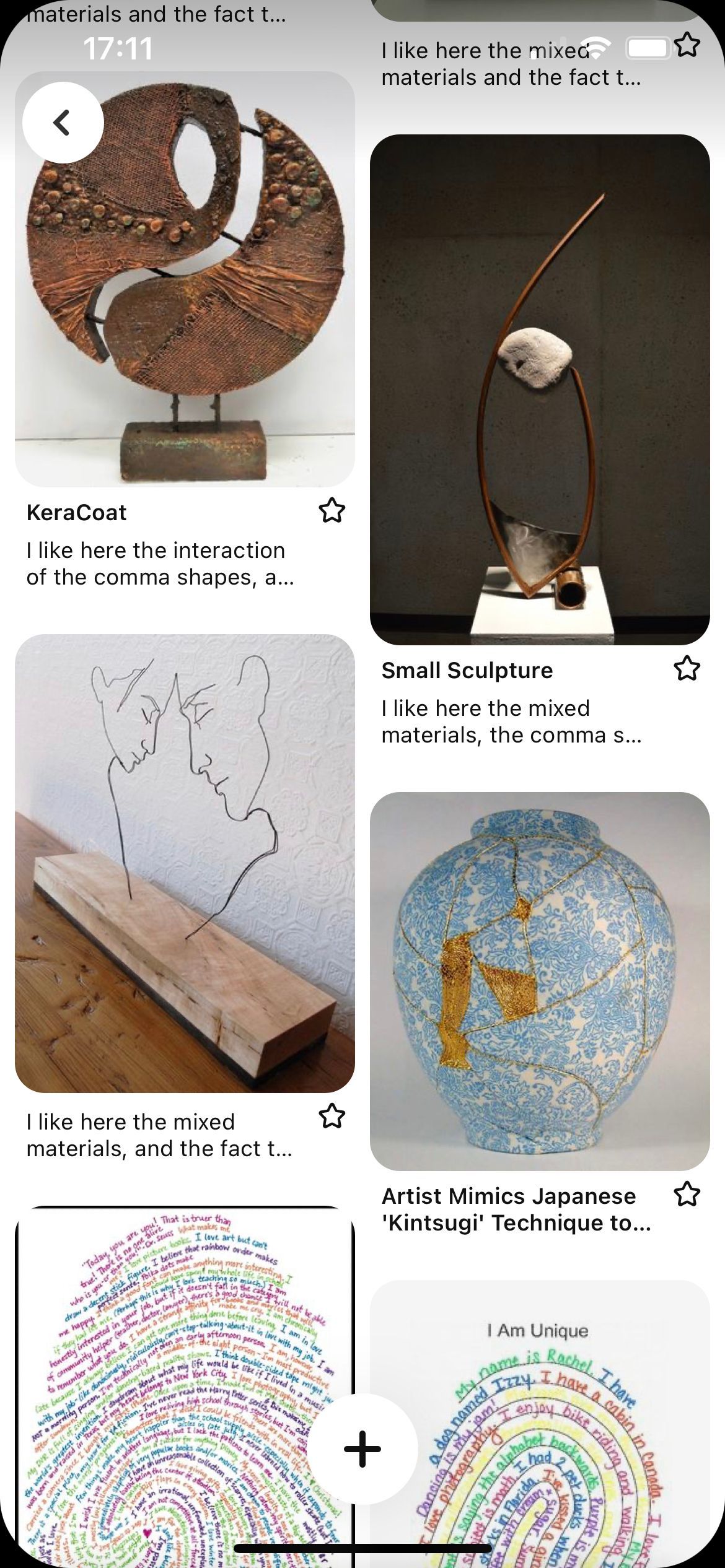

We agreed that I would produce three initial concepts that I would then present to the design group. The concept in the middle image was selected:

I then produced three iterations of this concept as below and the middle design was the one selected by the design group as the final design idea. This design has the form of a speech mark cut out from the edge of the award. A smaller speech mark is engraved onto the award with the new EFRJ strapline etched between them – ‘connecting people to restore just relations’.

In the next stage I refined the design as below to enable it to be constructed and created templates for cutting the components. The final design contained both wood (the award) and metal (the stand) as differing materials but with a relationship between them – the two materials are brought together when the award sits on its stand but separated when the award is removed from the stand.

Thus, each element of the award and its stand was designed to be symbolic. I now examine these elements:

1. The size of the award is based on a small plate (21.8cm) I use everyday at home. This size enables the award to be intimate, personal and familiar, easily and safely held.

2. The space carved out by the speech mark on the edge of the award signifies that it is impossible to be fully repaired or restored in the aftermath of harm or crime. When we have been people harmed through crime there is always a gap in our lives, a loss, and something that has been irrevocably taken away from us - we are not the same afterwards as we were before. This is why I sometimes question the word ‘restorative’ in restorative justice. A repair can be beautiful, however, whilst acknowledging the harm caused - as with the restorative process.

3. The wood chosen for the award is from the Yew tree which traditionally symbolises protection from harm. Yew is a tough wood yet elastic in its properties. I deliberately selected wood that contained ‘imperfections’. These were filled with purple resin that physically ‘repaired’ the wood and are visible on the front and back of the awards. Time and care was taken to decide on the colour of the resin with exchanges of ideas between me and the design group.

4. The award is multi-functional and designed to be removed from its stand to enable it to also be used as a talking piece in a restorative circle.

5. The award is deliberately designed to be displayed in its stand at an angle to indicate the imbalance of power created by the act of a crime being committed. Restorative justice can redress that imbalance through, for example, giving the person harmed a voice.

Finally, as may be seen from the image, there were four awards created – one to be presented every second year during the EFRJ conference over the next decade. The four awards were formed from one piece of wood as may be seen from the grain running through them all when viewed together. But, importantly, each is still unique.

All of the people involved in the design and fabrication of the award live in the Shetland Islands in the very north of Scotland or have family connections here. The making of the award, therefore, was relational and rooted in one place. Their fabrication involved four different people in addition to myself. I am deeply grateful to Cecil, Dawn, Keith and Ocean Kinetics who worked collaboratively with me to produce them. In particular, to Cecil Tait (and his sheepdog!) for creating the wooden part of the award and stand. To Keith Gorman for laser engraving the speech mark and lettering. To Dawn Siegel for engraving the metal stand with the EFRJ logo and name of the award. And to Ocean Kinetics for producing the metal component of the award stands.

Thus, interwoven with the awards is a notion of island-ness, and the specific relationality that island-ness brings. I knew of and now know better each of the makers and companies above through working closely with them on aspects of the award. I still hear about them, see them or bump into them as part of our daily island lives. As a way for the mainlander to fully understand this ‘density of acquaintanceship’ (Freudenberg, 1986, p. 27), Vannini and Taggart (2012, p. 230) invite us to imagine island living through the actions and embodiment of everyday life. For example, ‘Imagine waving at cars driving the opposite direction, regardless of whether you know the driver’. They thus describe island-ness as being defined by the practices of islanders (‘how do you do your island?’) instead of as a ‘representational entity’ and an abstraction. This changes island-ness ‘from a representation inside our heads to a set of tasks’ (Vannini and Taggart, 2012, p. 235). This is why it was so significant for me for the awards to come round full circle and not only be designed and made in an island setting but also to be presented in an island setting - during the 17th international conference of the EFRJ in Sassari, Sardinia. Massive congratulations to Siri Kemeny for being the first recipient.

As with islands, a design and making process is a dialogue that is never static but always changing as new information comes to light and new things are discovered and learned along the way. Much like the restorative process.

As a reflection, in this world of throw away goods, and mass produced objects and furniture, I hope in a small way the creation of the awards challenges how we perceive and understand designed objects. In the past, we would probably all have known the story and person/ people behind each item of furniture or each object in our homes. The maker of them would have been someone we knew or someone who lived nearby. Thus, there was a relationality between ourselves, our objects, and our communities. Consequently, I would also suggest a greater valuing of the designed object because of its embodied relationality. It would also have been more durable. Think about the heirloom pieces of furniture we may have received or the objects we treasure or miss if we lose our homes. For instance ‘consumers have a special appreciation for the human factor in production; handmade products are perceived to be made with love by the craftsperson and even to contain love…’ (Fuchs, Schreier, & Van Osselaer, 2015, p. 110). There is an understanding, therefore, that the handmade = an object characterised by love.

In the foreword to their book of collected essays, editors Moran and O’Brien (2014) describe what they call ‘love objects’ as those objects that can become conduits ‘for negotiating, materialising, and understanding relationships’. They state their aim in the book is not to ‘describe the objects’ but rather to unravel the times when love is ‘central as an emotion’. As Moran and O’Brien (2014) state in their foreword ‘objects become the foci of the authors’ attempts to grapple with the complexities of love as it is played out through the objects’ identities, both as possessions and as props in the performative enactments of social rituals.’

In an essay in the same book, Chapman (2014) describes love objects as being primarily ecological and sustainable, and as sharing the following criteria with ‘emotionally durable design’ (Chapman, 2015) - of being about: narrative (users share, and develop a personal history with the product); consciousness (products are autonomous); attachment (strong emotional connection to the product); fiction (the product inspires interaction and connections beyond the physical relationship); and surface (the product ages gracefully). In these ways, Chapman (2014) views love objects as emotionally durable design, and as a counter to our throw away society.

I hope that, in time, and as they are handled and used as talking pieces in restorative work, the awards will become just such ‘love objects’ and in so being challenge our throw away society. I hope also that in a tiny way the awards and the making of them cause us to reflect on our relationship with the designed object. In particular, the significance and beauty of a designed object, handmade in a particular place and time but having an ongoing relationship with us into the future - perhaps even outliving us for the next restorative generations. In so doing, being not only ‘love objects’ but also becoming examples of ‘emotionally durable design.’

References:

Freudenberg, W.R. (1986). The density of acquaintanceship: An overlooked variable in community research?

American Journal of Sociology (92)1.

Fuchs, C., Schreier, M., & Van Osselaer, S. M. J. (2015). The handmade effect: What’s love got to do with it? Journal of Marketing, 79(2), 98 -110.

Moran, A., & O'Brien, S. (2014). Love objects: Emotion, design and material culture [ebook]. Bloomsbury.

Vannini, P. & Taggart, J. (2012). Doing islandness: A non-representational approach to an island’s sense of place. Cultural Geographies20(2), 225 - 242.

Image credits:

I am grateful to Paul Wilkinson of Paul Wilkinson Photography for his photographs of the award. All other images in this blogpost are copyright Clair Aldington unless otherwise stated.